Travelling around Gran Canaria's unspoilt north, it's not difficult to imagine this as the land of the canarii, the Berber-descending people who occupied the island before the Spanish conquest. You'd even be forgiven for thinking you were going to bump into one. Especially so at Guía's Cenobio de Valerón.

The winding road to the Cenobio de Valerón

Located on the GC-200, the approach to the Cenobio de Valerón is a breathtakingly-spectacular one. Particularly, if you're travelling from Las Palmas de Gran Canaria and you turn off the GC-2 at the first signpost to the archaelogical site. The GC-200 winds it way around the mountainous Cuesta de Silva like a giant serpent.

For a less hair-raising arrival, continue towards Agaete before turning off at Llano Alegre. You'll then be able to loop back to the Cenobio de Valeròn, passing the Noroeste bathroom furniture showroom/restaurant. Make a pit stop here for its toilets as there are none on site and you're a mere two-minute drive away.

Where the eagles fly on a mountain high

If you suffer from vertigo, a visit to the Cenobio de Valerón's probably not a good idea. Although it's a unique setting for a yoga workout, which is one of the new activities on offer. You get a sense of how high you are above sea level when you see eagles and falcons in full flight, and look down on a ravine sculpted by over six million years of erosion.

Other fauna to look out for includes members of the lizard family. From big-daddy Lagarto Canario down to baby Perenquen. There's flora as well, including romero marino (sea rosemary) which features a flower with a distinctive pink blossom.

Upwards and onwards

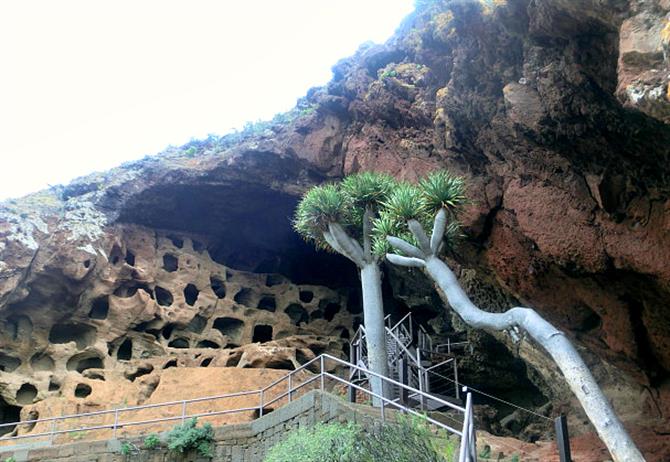

See those steps? You have to walk up those to reach the entrance where, after you've paid your standard 2,5 € admission fee, you're faced with even more to ascend to the attraction itself. Families with young children are best advised to leave pushchairs in the car.

This site's perilous position led historians to speculate the Cenobio de Valerón was a convent where the high priestesses of the canarii, the harimaguada, resided. That's what cenobio literally means, a monastery. It was a bewitching theory which lasted until the end of the 19th century when the French anthropologist René Verneau visited. He concluded the caves were generally too small to fit an adult in, shattering the vestal virgins myth in the process.

The granary of truth

In actual facts, the 200+caves are silos, carved out of the rock by the canarii to mainly store barley, their staple grain. Yes, the Cenobio de Valerón was a granary. It was located in such an out-of-the-way place to prevent attacks from neighbouring settlements as well as pirate raids. The dragon trees, dragos, you see are relative newcomers, planted in the 1970s. The canarii used the sap, known as dragon's blood as medicine and as a dye. The bark provided the wood for shields and the leaves fodder for livestock.

One of the nearest stone settlements was Layraga which you'll still see traces of in modern-day San Felipe. Here seagulls were ingeniously used by the canarii to thwart the Spanish invaders. What the canarii would do would be to capture four or five gulls and tame them, so they became domesticated. Then they'd leave them on display and head for the hills when they saw a boat approaching. The seagulls, by now used to humans, would sit motionless as the marauders advanced. This gave the new colonels a false sense of security as they assumed Layraga was abandoned. Only to be surprised by the returning canarii, launching an attack from above.